Amudat, Uganda — Sitting at her desk in a classroom at Kalas Girls Primary School in this remote town of northern Uganda, 15-year-old Susan Cherotich narrated through tears how she had fled her parents’ home some six weeks earlier following pressure from her uncles and elders to marry before she completes her education.

The eighth-grade student said her parents were opposed to the idea, but the decision by the majority of her clan members to start a home with a man was more binding, a common practice in her Pokot tribe.

Susan said her uncles and elders wanted to sell her against her will into marriage for dozens of cows to an older man she had never met.

“I heard that the man had several wives, and he was willing to give out many cows,” she said.

“I left at night after realizing they were coming to marry me off.”

She took refuge at a police station before religious sisters took her to Kalas Girls Primary School in Amudat parish, run by the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Reparatrix-Ggogonya. “My father pleaded with his brothers and elders to let me finish school, but they objected, saying it was the right time for me to be married off since schools were taking a long time to resume due to the COVID-19 lockdown.”

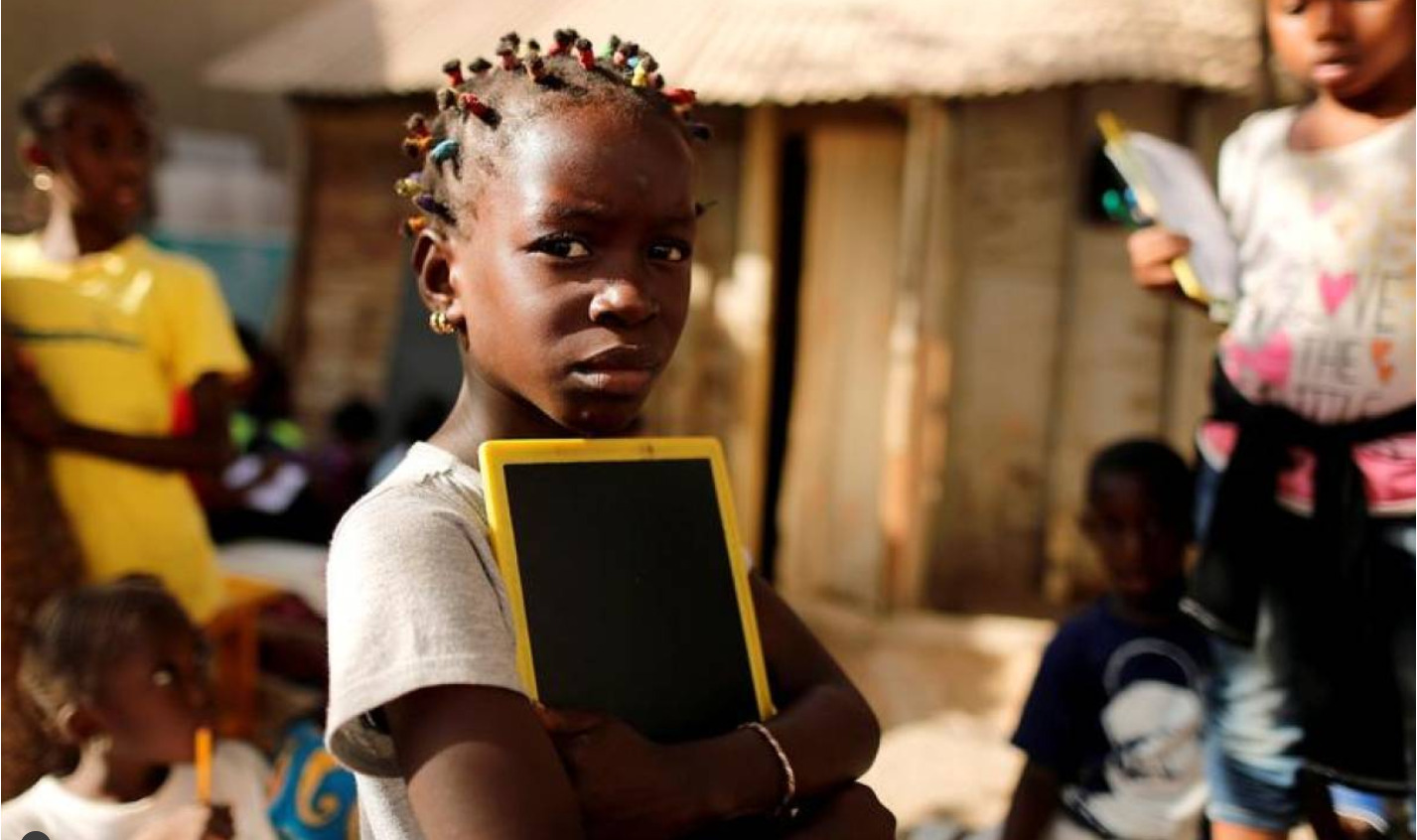

Susan is among thousands of girls in northern Uganda who have been rescued from marriages they did not want and taken to Kalas Girls Primary School, which is also sponsored by UN Women, UNICEF and the World Food Program. The boarding school provides hope and a haven for girls who have escaped genital mutilation and child marriage. At the school, the girls receive counseling and psychosocial support.

The East African nation is one of the countries with the highest rates of early and forced marriage, according to a 2019 report by UNICEF: The country of more than 45 million people is home to 5 million child brides. Of these, 1.3 million married before age 15, UNICEF reports.

The report also notes that child marriage results in teenage pregnancy, which contributes to high maternal deaths and health complications like obstetric fistula, premature births, and sexually transmitted diseases. It is also the leading cause of girls dropping out of school.

The practice is widespread in rural areas such as Amudat, where there are high levels of illiteracy, poverty and unemployment, UNICEF notes. Parents in many communities here bring up daughters for a single purpose: to sell them when they are children into marriage for cows, which are considered a key source of livelihood and a symbol of wealth and success.

“People in this area consider marriage as a shortcut to benefiting from a girl child [more] than education, which would require them to spend money on tuition. Educating a girl is seen as a loss to majority of residents here,” said Haji Shaikh Waswa Masokoyi, the chief administrative officer of Amudat. He added that a girl fetches between 40 and 50 cows. “These forms of gender-based violence have escalated during the COVID-19 lockdown [that was in effect from March 2020 to January 2022]. Over 300 girls are estimated to have been married off during the lockdown.”

Sr. Maria Proscovia Nantege, headmistress of Kalas Girls Primary School, works with the police and other agencies to ensure girls are protected from early marriage and that those rescued are offered a haven before they are reintegrated back with their families. The sisters also provide the girls with basic education and vocational training in tailoring, sweater-making, beadwork and hairdressing.

Nantege said they began the program in 2017 after reports from police, local officials and other agencies showed an increase in the number of girls who were being married off in the region.

“We came here to see how we can help the girl child because of the cultural practices being carried out by the community,” she said, noting that their efforts were successful until the government-imposed lockdown to fight COVID-19. “It became worse during the lockdown because girls were dormant at home, and some parents deceived their girls that the lockdown would take five years and so they needed to be married off.”

Nantege said since the program started, they have been able to rescue over 1,000 girls. These girls are usually brought in by the police, or sometimes the girls refuse to go home after schools close, especially when they know a marriage proposal has been arranged, she said.

However, Nantege said not all girls forced into early marriage seek help from the sisters or elsewhere. Only a few who have a vision of completing school and are not comfortable with the proposed spouses seek help, she said.

“The police pick the girls from the villages, but girls sometimes come here directly, and we inform the police about it. We have been working hand-in-hand with the police and other local leaders,” she said. “Our main objective is to provide education to the children. Still, sometimes we do counseling because some of those girls are usually traumatized from the experiences they have gone through. Funding for school fees for these girls is usually the main problem, and we are regularly looking for well-wishers to help us.”

The sisters said the rights of the girls who have gotten married have been violated, including the right to education, freedom from violence, reproductive rights, and the right to consensual marriage.

Fourteen-year-old Esther Nangiru says her parents violated her rights, and she had to run away from her husband last year after he assaulted her.

“My parents forced me to get married when I was 12 years old because they had received cows from my former husband,” she said, adding that her husband would frequently get drunk and beat her. Esther ran away from her home and took refuge at Kalas Girls Primary School.

“It pains me that I had to drop out of school,” Esther said.

Although she is still married, Esther says she will never go back to her husband. She plans to stay in school and learn life skills.

Sr. Dorothy Sserabidde said the sisters have been carrying out an awareness campaign in churches, villages, schools and markets, talking to young people, parents and elders about the dangers of child marriage and female genital mutilation.

“We keep talking to the people in the communities not to force their girls into early marriage and instead allow them to pursue education and achieve their dreams,” said Sserabidde, who is also a teacher at Kalas Girls Primary School. “However, it’s a process since it is a cultural practice rooted in their hearts and minds.”

Susan agreed but appealed for strict measures against the perpetrators.

“They should arrest those elders and parents forcing their daughters to get married against their will,” she said. “They are killing our dreams and violating our rights.”

![Thanks to an initiative by local NGO MJAS, football has helped girls from Ajmer district in Rajasthan state overcome societal taboos [Valay Singh/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Football-team-Meeno-ka-Naya-Gaon.jpg?resize=770%2C513)

Indian advocacy group Jan Sahas believes there are an estimated 100,000 women and girls in caste and gender slavery. Photograph: Rebecca Conway

Indian advocacy group Jan Sahas believes there are an estimated 100,000 women and girls in caste and gender slavery. Photograph: Rebecca Conway